The Maritime Oxypathor Co.

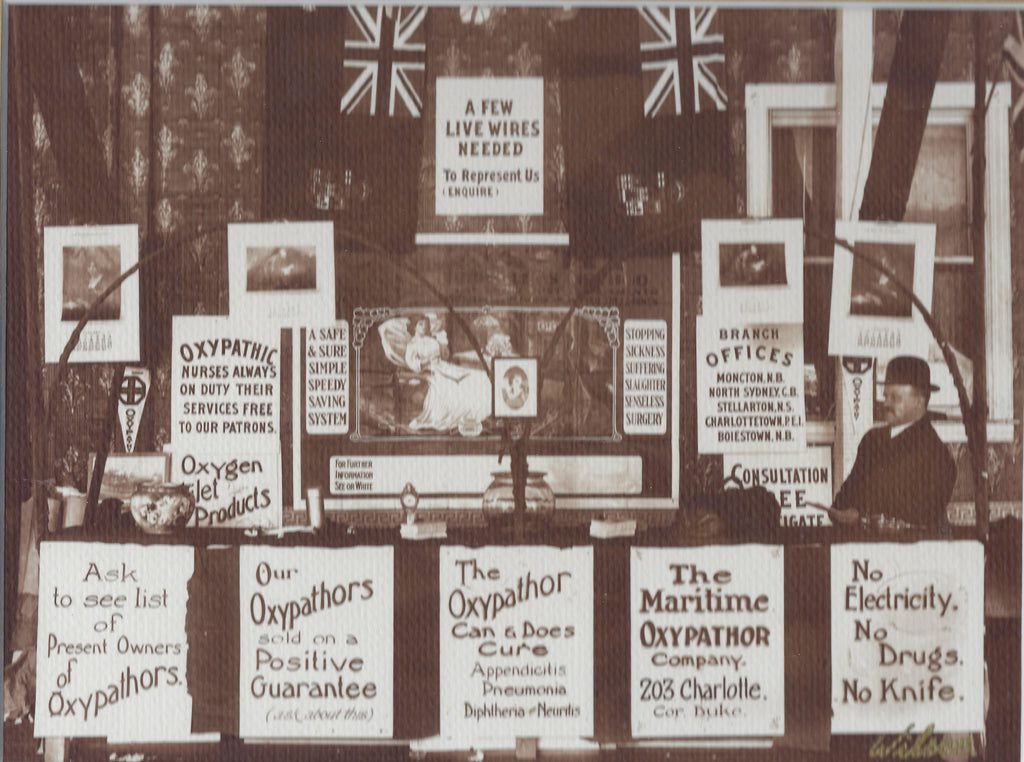

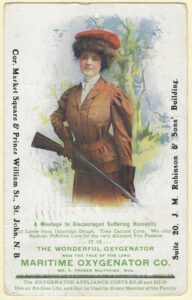

Imagine a company promoting its health product, as being capable of curing any disease that can be cured. It sounds reminiscent of a travelling medicine show, but the reverse side of this Saint John, New Brunswick store card reads, “the marvellous oxypathor lasts for life / cures any disease / that / can be cured / our literature / is free / ask for it”. The obverse side states that one should, “See our exhibits and remember especially / our new address / The / Maritime / Oxypathor Co., / 203 Charlotte St., / cor. Duke / C. Fraser MacTavish / General Manager / Tel. Main 2367 / St. John, N.B.”.

Here was a Saint John businessman making this claim, and inviting people to examine for themselves this amazing piece of medical equipment. It would have sounded like a godsend for those afflicted by any imaginable, curable ailment, but it now sounds too fraudulent to have been believed. This raises a couple of questions. Why was advertising, that today would be viewed as criminally misleading, so widely accepted? Secondly, who was C. Fraser MacTavish, and what is the Oxypathor?

Outrageous advertising. Why would people believe it? To get an answer to that question, you have to examine what the alternatives were. Conventional medicine in the twentieth century has been of a high standard, improving with each generation of physician. Patent medicines on a large scale began in the nineteenth century, and in the early part of that century, patient confidence in medical practitioners was at a low point, due to very dangerous and questionable medical techniques. Physicians practised a form of medicine labeled as heroic, where the key words were bloodletting, calomel, and blistering. Bloodletting was a standard therapy until after the U.S. civil war. By use of the lancet or leeches, blood was removed from the body, often until the patient lost consciousness. Doctors treated the visible signs. Therefore if patients had a fever, bloodletting would alter their flushed appearance to a state of pallor. Calomel, or chloride of mercury, also brought about quick, violent results of little therapeutic value. Continued use resulted in mercury poisoning. Blistering was a technique that encouraged the infection of wounds. There were also the fringe movements, such as the one led by Samuel Thomson, who attacked the opium and mercury of conventional medicine in favour of his patented system of botanical medicine. His organization flourished for more than two decades, but internal splintering, and a new age of specialization, caused its demise. What filled the void was a new age of patent medicine.

From the 1870’s to well into the 1930’s the new patent medicines promised to cure everything from ‘female diseases’ to cancer, without discomfort and generally without addiction. The list of remedies, such as Lydia E. Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound, Kickapoo Indian Sagwa, Roger’s Cocaine Pile Remedy were as numerous as the therapeutic claims of the manufacturers. The popular remedies were often alcohol, opium, or cocaine based. Some of the earlier treatments, based on the premise that the worse it tastes the better it is for you, were primarily cow urine and dung.

In 1906 Sears, Roebuck and Company catalogue carried twenty pages of their house brand patent medicines. As Stewart Holbrook, in his book The Golden Age of Ouackery describes the advertisement for Sears White Star Secret Liquor Cure. “The Sears ad showed Mother furtively slipping the cure into Daddy’s coffee, and intimated that after a few doses Daddy would cease helling around nights. The White Star nailed him home for sure. Analysis showed it contained sufficient narcotic to put him to sleep as soon as he could reach the kitchen sofa right after supper. If, as it could have turned out, Daddy became a confirmed narcotic addict, in the same department of the catalogue was an advertisement for Sears Cure for the Opium and Morphine Habit.” In 1907 the Pure Food and Drug Act was passed, but it did little to change the contents of the patent medicines, as the manufacturers only had to list the contents on the label, not alter them. Many manufacturers rallied in support of the Act, as they were able to legitimize themselves through it. There was also the new technology: no drugs, but devices that would give the body an electrical charge, or inject oxygen into the system. These devices were the equivalent of a modern day placebo, as any improvement in the patients’ condition was in their own minds. These alternate forms of medicine were still in many cases less harmful than the doctor, and less costly. Medical techniques had improved greatly by the turn of the century, but there was still a large segment of an entire generation who would gamble on patent medicine. A large enough segment, that in 1905, patent medicines were a seventy-five-million-dollar-a-year industry.

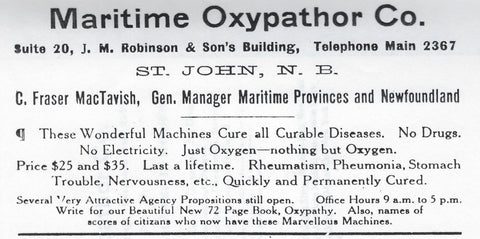

The Maritime Oxypathor Co., was established in Saint John during the year 1910. Initially the company was known as the Maritime Oxygenator Co., and it was under this name that they exhibited in the Dominion Exhibition during September of 1910. An advertisement in McAlpine’s Saint John City Directory for 1911 lists them with the Oxygenator changed to Oxypathor, and also shows them occupying suite #20 in the office building of the private banker, I.M. Robinson and Sons at 19 Market Square.

It was in 1912 that the company moved to 203 Charlotte Street, and since the store card requests that their new address be remembered, it is reasonable to speculate that the piece was issued in 1912.

The company was no longer in business by 1916, but C. Fraser MacTavish was still at 203 Charlotte Street, acting as a representative of the Violet Ray Sterling Corporation. What is known of C. Fraser MacTavish? Unfortunately little. He is first listed as a resident of Saint John in 1910, so it would appear that he moved to Saint John to establish his Oxypathor agency. His business strategy, or at least as much as one advertisement will divulge, was divided amongst two areas. As the general manager for the Maritimes and Newfoundland, he was trying to open up additional agencies in order to broaden the market for the Oxypathor. The public would be willing to send perhaps a couple of dollars through the mail for a packet of Lloyd’s Cocaine Toothache Drops, or a bottle of Peruna, but the Oxypathor was more than a week’s wages for a labourer, and that would require a demonstration and a sales pitch. He was also interested in not so much as selling lo the public from the advertisement, but in raising public awareness in his product, to the point where they would write or telephone to receive a 72-page booklet entitled Oxypathy. This booklet would make the sales pitch, and further inquiries would lead to the demonstration, and eventual sale.

What was the Oxypathor technique? Fortunately the American Medical Association takes a dim view of quack medicine, so the Oxypathor and dozens of other similar companies are well documented by the A.M.A. It appears that the Maritime Oxypathor Co., was a distributor for the Oxypathor Co., of Buffalo, New York. The latter company, was established in 1906, was a major player in what is referred to as the “gas-pipe cures”. This technique was developed by one of the most infamous of American patent medicine pioneers, Hercules Sanche. Sanche, marketed his device under the name of the Oxydonor. His device, like the later Oxypathor, was described as, “a piece of nickel-plated piping, closed at both ends and filled with some inert and inexpensive substance. To the piping were attached one or two flexible wires, at the free ends of which there were two small disks with elastic bands and buckles, so that they could be fastened to the wrist or ankle, or both, of the user ” 1 The cylinder was then placed into a bowl of cold water, the result being a “thermo-diamagnetic force”. This force would allow for large quantities of oxygen to pass through the pores of the skin. What would this do to the body? The company claimed that its equipment, “when attached to the human body, alters its magnetic properties, greatens its affinity for oxygen, and thus increases the body’s capacity to attract and absorb the oxygen of the air, and further, that the use of the machine… will quiet the most agonizing pain in a marvelously short time, give profound, restful slumber, stimulate and arouse the body and all its organs to renewed vigor, and cure practically very disease.”2 All this for only $25.00 or $35.00, depending upon model, with special treatment plates for certain diseases available at extra cost.

Skeptical? Apparently a committee appointed by the British Parliament to investigate medical frauds was skeptical enough to call it a deliberate swindle. The Australian government went a step further, and banned the product from the continent. In the United States there was a two-prong attack against the Oxypathor, by the American Medical Association and the U.S. Postal Services. While there were several different companies promoting their own variations of “gas-pipe cures”, the A.M.A. singled out the Oxypathor Co., for its vicious advertising. The Golden Age of Ouackery, quotes from one of the Oxypathor’s pamphlets, “Diphtheria finds its supreme master in the Oxypathor. No earthly power, except the Oxypathor can take the slowly choking child, and with speed, simplicity, and safety bring it back to health.” The A.M.A.’s response in their journal, was that it was a, “cruel and criminal lie”. For defrauding through the mails a willing public, the post office successfully prosecuted Elvard L. Moses, general manager of the Oxypathor Company. On November 7, 1914, he was sentenced to eighteen months in jail. In March and April of 1915, several other U.S. branch offices had fraud orders issued against them.

No ailing individual was ever helped by the Oxypathor. The testimony by users and doctors, given as evidence at the trial, was valueless. The users either imagined their diseases or recovered, with or without treatment by doctors. In the case of doctors supporting the Oxypathor, it was found that their patients were also getting conventional medical treatments, or that they, the doctors were sales agents for the Oxypathor Company. C. Fraser MacTavish, and the other distributors were willing participants in this fraud. In a sales memorandum to agents, they were told to, “tell yourselves repeatedly that the Oxypathor is all right. Repeat this until firmly convinced that it is all right. Thereafter you will be invincible.”3 There was only one reason for the manufacture of the Oxypathor: a selling price of $25.00 to $35.00, manufacturing cost of a $1.23, and 45,451 units sold between 1909 and 1914.

Bibliography

Armstrong, D. & E.H. (1991): The Great American Medicine Show. Prentice-Hall, New Y ork.

Cramp, Arthur, (1912,1921): Nostrums and Quackery. American Medical Press. Holbrook, Stewart H. (1959): The Golden Age ofQuackery. McMillan Co. New York. Stage, Sarah (1979): Female Complaints: Lydia Pinkham and the Business of Women’s Medicine. W.W. Norton & Co. New York.

Conespondence with Staff of the New Brunswick Museum, Saint John.